Associates |

| Neilson & Barbara BrownJohn Ford Vallejo Gantner Rev. Mark A. Matthews Henwar Rodakiewicz Cornelia Runyon Paul Strand Fred Zinnemann |

| Neilson & Barbara Brown |

|

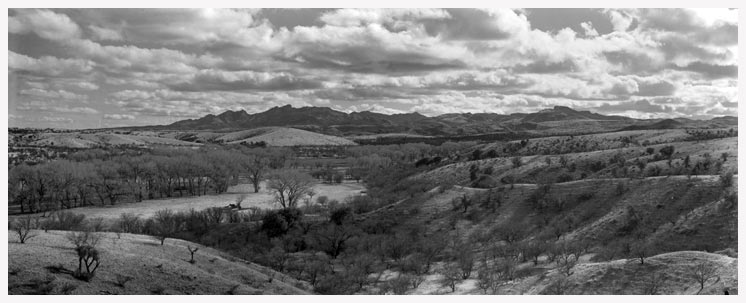

| Neils and Babs Brown were Easterners, like Ned Scott and many of his associates, who decided in the timeframe of the ’30’s to migrate West and create new lives. The Browns bought an 1800 acre cattle ranch called the Buena Vista located on the outskirts of Nogales, Arizona. Portions of the boundary of this large ranch bordered Mexico. They built a typical hacienda in the style of the area, surrounded it with an ocotillo fence, and made a very decent life for themselves and their two sons. Neils Brown was later to become an Arizona State Senator who served his constituents with distinction. Ned Scott and his new wife found themselves visiting the Browns and their beautiful ranch as often as they could during the latter half of the ’30’s and early ’40’s. Ned’s associates also wended their way to the ranch from time to time. Wonderful parties were held there. It was the southern anchor for their wanderings around Arizona in those days. Always stimulating, the ranch provided reinforcement for a new style of living and looking at the world. Ned Scott photographed the ranch views and the interiors and exteriors of the hacienda. He also created portraits of the Brown family. All these images reflect a renewed purpose and zest for life which had previously eluded him in New York. The friendships were strong and lasting. As 1942 dawned on a nation newly at war, Ned and Gwladys approached the Browns to serve as godparents and protectors for their newborn daughter, just 10 months old. Ned had just been selected by Orson Welles to serve as still photographer for Carnival, a film set on location in Rio de Janiero, Brazil. He was to be out of the country for an unspecified period of time, and things were very uncertain. |

| John Ford |

|

| Vallejo Gantner |

|

| Rev. Mark A. Mathews |

|

| Henwar Rodakiewicz Ned Scott met Henwar Rodakiewicz after he joined the Camera Club of New York. Their friendship was to last until Ned’s death in 1964. Ned faithfully kept all Henwar’s letters over many years, one of which is displayed here. Henwar was very well connected to those on the leading edge of photographic artistic expression. He was a practitioner himself, preferring natural forms found in nature which were uncluttered by human thought or feeling. Cloud formations were particularly strong subjects for Henwar. Scott took up the idea himself in his own nature photography. Henwar distinguished himself as a documentary film maker. Among his better known efforts are Portrait of a Young Man in 1932 and Georgia O’Keeffe in 1947. What is not generally known about Henwar’s contribution to the world of film is his uncredited assistance on the projects which others conceived and started. Some notable productions on which Henwar collaborated are Paul Strand’s Redes in 1934 and Ralph Steiner’s The City in 1938. oth of these productions would have languished and failed were it not for Henwar’s worthy assistance. He stepped in as writer, director and cameraman, whatever was required to keep things afloat. He was the fixit man, and with his vast connections, accomplishments were the happy outcome for others. He was a man devoted to his genre. In 1962, sensing the inevitable, Ned Scott gave all his photographic equipment to Henwar. |

A letter from Henwar Rodakiewicz, November 7, 1932 |

| Cornelia Runyon |

| Cornelia Runyon was an artist by temperament, and later in life, an artist for real. Besides that she was a wife, mother and a social center. Ned Scott went to her home in Brentwood, California some four months after returning from the Mexican film project with Paul Strand. That evening, he met Gwladys von Ettinghausen, a screen writer with MGM, the woman who eight months later would become his wife. But it was the other people at the gathering that night who were to be key components to his future as a still cameraman in Hollywood. Agnes De Mille has written that the majority of Cornelia’s acquaintances in those years were members of the “moving-picture” colony. It was these personages that Ned Scott encountered as he visited Cornelia’s Brentwood home in the years of 1935 and 1936, along with, one must presume, the other “Zopilotes” (his transplanted Mexican crew). He made important contacts. Prints which he brought with him to these gatherings were passed around. See Clara B. de Mille letter. Discussion took place. He must have made a very favorable impression on this Western crowd, this man from New York, because he was given a very important assignment very early in his career. That assignment was the still work for “The Good Earth”. He was equipped and ready to go on the job, but for one thing. He discovered on the eve of filming that without a union card, he could not perform his task. A bitter lesson learned. That Cornelia was a huge boost in those years is undeniable. She remained a close friend through the ’50’s, often inviting the Scott family to her spectacular new house overlooking the palisade cliffs just north of Malibu. Built and finished just before Pearl Harbor Day, 1941, this house became the locus of her art career as a sculptor. She worked in natural stone, gathered there just below her house on the rambling and wild beaches of the region or on trips to the desert areas nearby. She had her first curated one man exhibit at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1961. |

|

| Paul Strand |

|

| Fred Zinnemann |

|